Dubbed “the best of days” by the poet Catullus, the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia was one of the most widely celebrated festivities in the Roman world – a weeklong event dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture and harvest and coinciding with the winter solstice and one of the most widely celebrated festivities in the Roman world. Decorating, feasting, gift giving and overall merriment were all part of the festivities, and draw parallels to modern Christmas, but Saturnalia was also included a unique celebration unto itself.

The Origins of Saturnalia

Saturnalia initially began as a single day event celebrated on December 17th (in the Julian calendar) dedicated to the agricultural deity Saturn whose temple in the Forum was the center of sacrifices for the holiday. By the late Republic, the festivities expanded to a week of merrymaking. However under Augustus, the holiday was officially reduced to three days.The festival coincided with the winter solstice, symbolizing the end of the agricultural season and the hope for renewal and abundance.

Caligula (imagine that!) extended the festivities to five days and ordinary Romans, in practice, often celebrated for the full seven days despite official decrees. Roman historian Livy believed Saturnalia began in the 5th century BCE, though it may have originated even earlier. By the 5th century CE, Saturnalia was still being observed, as noted by Macrobius in his work Saturnalia. The festival’s longevity and popularity underscore its cultural significance.

Public and Private Celebrations

The festival began with a public sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum, followed by a communal banquet. Private celebrations included gift-giving, feasting, continuous partying, and a carnival-like atmosphere that overturned traditional social norms.

Role Reversals

One of Saturnalia’s most striking features was the temporary suspension of cultural hierarchy. Enslaved people were allowed to mock their masters, who in turn served or dined alongside them. Masters wore the pileus (felt cap) of freed slaves to symbolize this reversal, creating an atmosphere of liberty for all.

King of Saturnalia

A popular custom was the election of Saturnalicius princeps (king of Saturnalia). Chosen by lot, the “king” presided over the festivities, issuing humorous or absurd commands that guests were obliged to follow. Orders like “Sing naked!” or “Throw him into cold water!” added to the chaotic and playful spirit. The future emperor Nero is even recorded as playing this role in his youth.

Gambling and Merrymaking

During Saturnalia, activities like gambling, normally restricted or frowned upon, were openly embraced. Dice and knucklebone games became a staple, with coins or nuts as stakes. A famous depiction on the Calendar of Philocalus shows a man in a fur-trimmed coat playing dice beside a caption: “Now you have license, slave, to game with your master.” Overeating and drinking were also hallmarks of the festival, with sobriety being the rare exception.

Gift-Giving and the Sigillaria

The festival concluded with the exchange of symbolic gifts, such as candles, jellied figs, knucklebones and small terracotta figurines called sigilla. These items were sold in a special market called the sigillaria, which lent its name to the final day of Saturnalia. It was also customary for masters to give money to their dependents so they could participate in the gift exchange.

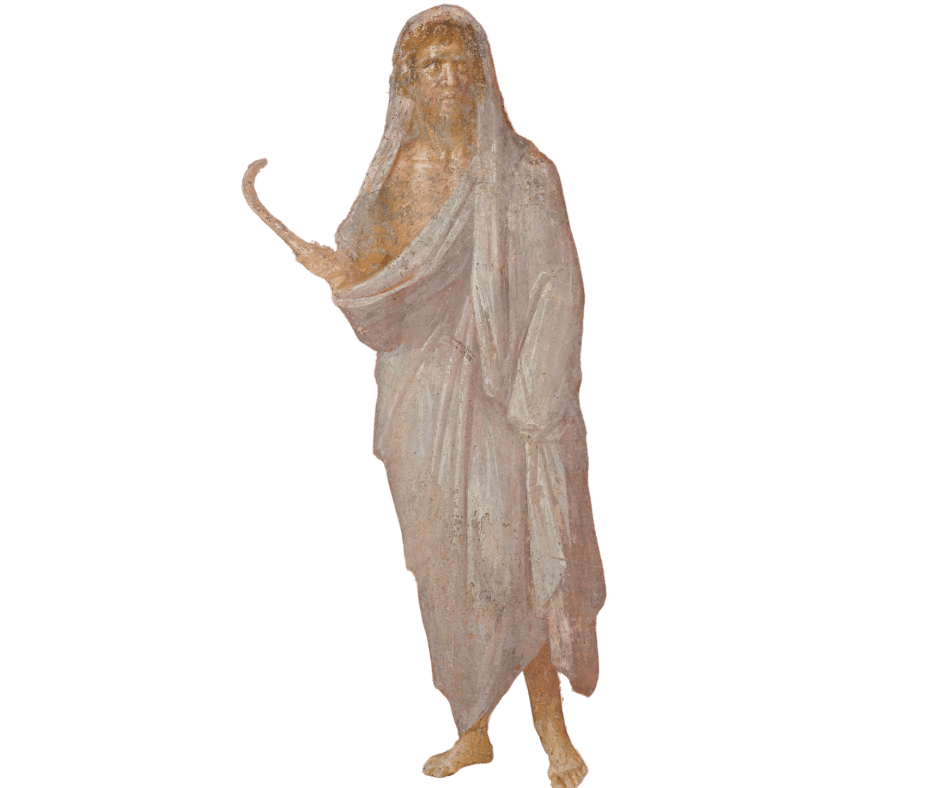

The Temple of Saturn, located in the northwest corner of the Roman Forum, was the focal point of the festivities. Originally built around 497 BCE, it housed a statue of Saturn whose feet were typically bound with woolen straps to symbolize control over chaos. During Saturnalia, these bindings were removed, representing freedom and release.

Saturn was closely associated with the mythical Golden Age, a time of harmony, abundance, and equality. The festival honored this idealized era, inviting Romans to momentarily cast off the rigid structures of their society and embrace joy, generosity, and hope for renewal.

The spirit of Saturnalia lives on in today’s winter holiday traditions, with its focus on joy, community, and generosity reminding us of our timeless need for connection and celebration during the year’s darkest days. So step outside and let the world hear you: Io, Saturnalia!

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: Darius Arya, The American Institute for Roman Culture, “Saturnalia – The Jolliest Week in Ancient Rome” Ancient Rome Live. Last modified 22/01/2025. https://ancientromelive.org/saturnalia-the-jolliest-week-in-ancient-rome/

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 22/01/2025 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.