Written by: Amineddoleh & Associates LLC

In our previous article for Ancient Rome Live, we discussed the history of looting and illicit trafficking of cultural goods, including its role in the art market and its effect on national and international laws and policies. In this article, we will explore various legal tools that are used to fight the destruction, looting, and illicit trafficking of cultural goods, as well as the challenges countries face in approaching these issues.

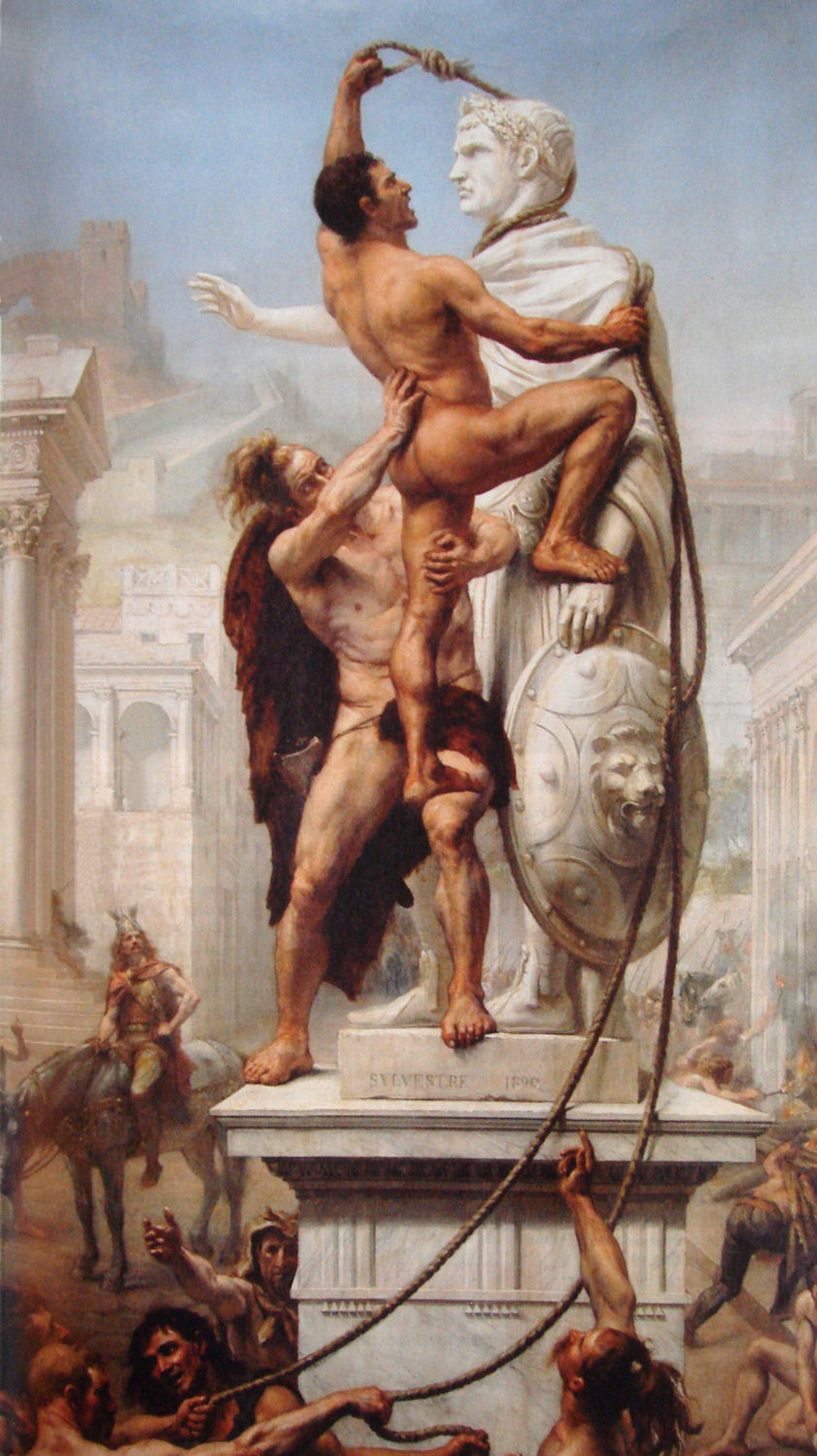

Sack of Rome by the Visigoths on 24 August 410 by JN Sylvestre 1890

Destruction of Cultural Goods

It is “brutal rage and madness to destroy things, the destruction of which does not in the least tend to impair an enemy’s strength, nor to increase that of the destroyer: Such are Porticos, Temples, statues, and all other elegant works and monuments of art…it is a mark of reverence to divine things to spare them, and all that is connected therewith…” Hugo Grotius’s treaties On the Law of War and Peace (1625) is sometimes cited as one of the first works to mention the importance of protecting cultural heritage during war. The protection of cultural heritage took form as part of the international community’s larger legal effort to regulate the “laws of war.” In 1863, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Lieber Code (the “Code”) during the American Civil War to regulate the protection of property, which included cultural objects. This represented a concerted effort to create a framework for the protection of cultural heritage. The Code recognized that the risks to heritage are heightened during times of armed conflict. Under the Code, works of art and cultural objects were to be “secured against all avoidable injury,” even if located in places that were subject to military attack. Additionally, these objects were not to be looted, sold, given away, or privately appropriated. The Lieber Code set the foundation for other international treaties, including the Convention with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land (the “Hague Convention of 1899”). While this Convention was written with the broad goal of limiting physical damages during war times, it is considered a landmark document for the protection of cultural property. In 1907, a subsequent iteration of the Convention upheld that cultural property should be shielded from conflict and considered worthy of protection.

World War II’s unprecedented destruction of cultural property prompted the international community to draft the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (“1954 Hague Convention”). The 1954 Hague Convention was the first major international text entirely devoted to the protection of cultural property, which it defined as movable and immovable heritage of “great importance for the cultural heritage of people.” The Convention and its Second Protocol (1999) created a universal responsibility for all States and citizens to protect each other’s cultural heritage in the context of military conflicts. Notably, the language in the 1954 Hague Convention does not delineate degrees of protection based upon the types of objects, their origin or ownership; rather, Art. 1a has a broad definition of cultural property that allows for more expansive protection of tangible, intangible, public and private objects. Whether the object possesses “great importance to the cultural heritage of every people” is the key factor in determining its protection.

In 2012, the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) issued a verdict that recognized the intentional destruction of cultural property during armed conflict as a war crime under the 1998 Rome Statute. In 2021, the ICC’s Prosecution Department drafted a Policy on Cultural Heritage that discussed the link between the destruction of cultural heritage and its harm to human rights. The destruction of cultural property represents a substantial loss for both specific cultural groups and humankind in general.

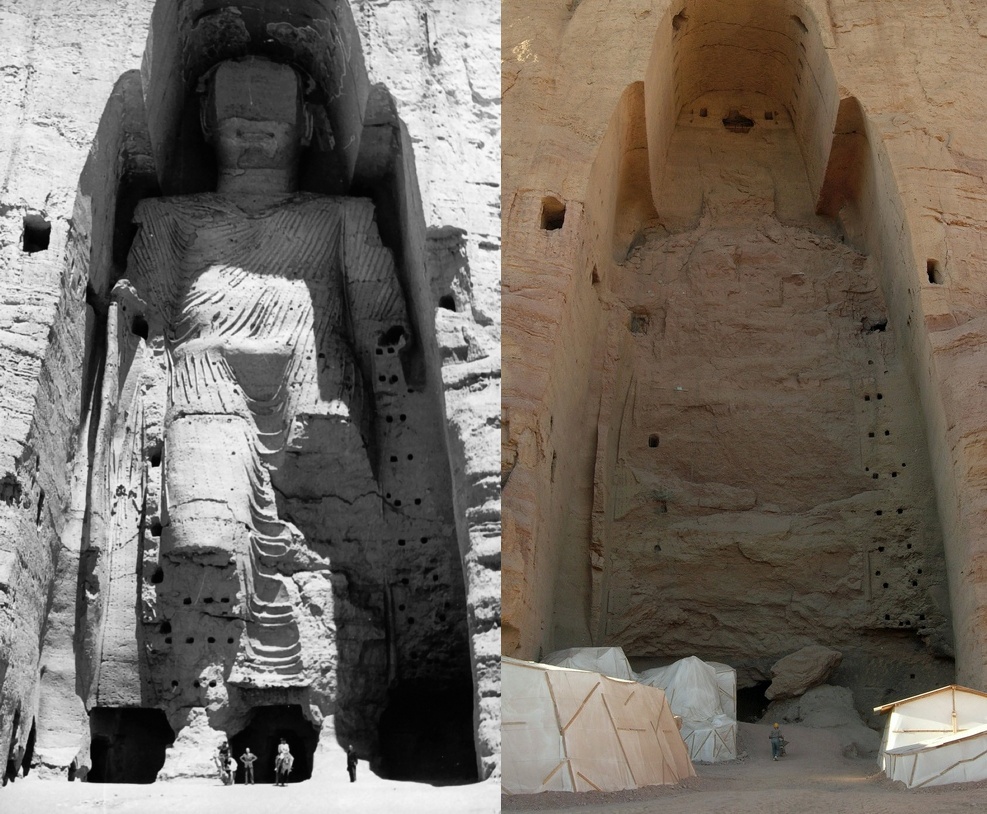

Taller Buddha of Bamiyan before and after destruction

The destruction of cultural property also takes place outside the context of armed conflict and has, in some cases, been used as a form of propaganda. One of the more infamous examples of destruction in the name of propaganda took place in Afghanistan when the Taliban terrorist group obliterated the Bamiyan Buddha statues to end of the worship of “idols.” The two Buddhas dated back to the 6th century and measured 125 and 180 feet respectively, heralding the Silk Road for travelers. In 1221, Genghis Khan attacked the area but spared the Buddhas. Over the following centuries, numerous military leaders targeted the statues but were unable to demolish them completely. In 2001, the Taliban used dramatic videos of the destruction to notify the world of this crime against heritage. The destruction was carried out in stages, with the use of guns, artillery and explosives. It was described as a “crime against culture” by Koichiro Matsuura, the Director General of UNESCO.

Looting of Cultural Goods

Fifteen years after the Hague Convention responded to the destruction of cultural property in the context of war crimes, UNESCO drafted the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (“1970 Convention”) as a response to frequent looting of museums and archeological sites. The 1970 Convention urges international cooperation to prevent illicit trafficking and provides a legal framework so that Member States can make restitution requests for objects inventoried and stolen from a museum, public or religious monument, or similar institution. The 1970 Convention’s implementation of this framework, however, depends on other international organizations, national governments and law enforcement, and judicial authorities.

The Secretariat to the 1970 Convention regularly urges its Member States to ratify the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects (“1995 Convention”). UNIDROIT, an intergovernmental organization based in Rome, addressed gaps in the 1970 Convention when they drafted the 1995 Convention at the behest of UNESCO in order to provide a private law mechanism for the return of stolen, looted and illicitly exported cultural property. While the 1970 Convention gives Member States the option to “opt-out” of certain provisions, UNIDROIT aims to harmonize State legislations. In addition to the obligations on the Member States, the 1995 Convention also places a due diligence obligation on art and antiquities buyers. Article 4 states that due diligence requires buyers to pay special attention to the entire acquisition process of an object, such as “the character of the parties, the price paid, whether the possessor consulted any reasonably accessible register of stolen cultural objects, and any other relevant information and documentation which it could reasonably have obtained.” Perhaps because of its more constraining nature, the 1995 Convention has only been joined by 50 States. Italy ratified it on April 1, 2000.

In addition to international treaties and national laws (discussed below), law enforcement plays a key role in the protection of cultural property, which must be safeguarded for humanity and its future generations. Italy’s Carabinieri for the Protection of Cultural Heritage and Anti-Counterfeiting (TPC) has been an essential ally in UNESCO’s mission. As a hub of ancient art, Italy is especially prone to looting and theft. The TPC is one of the foremost – and earliest – specialized national law enforcement groups dedicated to the protection and restitution of cultural property. Since its inception in 1969, the TPC has participated in dozens of investigations at both the national and international level, and it has created a database that catalogues stolen artwork (aptly called Leonardo). In 2014, the TPC developed an app that allows members of the public to access the database. In order to regulate and mitigate online trafficking, the Carabinieri Headquarters for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (“TPC”) signed an agreement with eBay allowing it to enter into the website’s system and database in order to retrieve suspicious users’ personal information. This allows the TPC to better trace objects with a potentially looted origin and expose trafficking networks. As a result, Italy has experienced great success in promoting the importance of its cultural heritage, establishing relationships with key partners on the global stage, and recovering stolen, looted and illicitly exported objects from abroad.

Carabineri TPC, located in central Rome, Piazza di S. Ignazio

Patrimony Laws

Patrimony laws are laws that protect cultural heritage by vesting their ownership in the State. In other words, under patrimony laws these cultural sites are considered state-owned property. This does not necessarily prevent individuals from owning, selling, or purchasing cultural property, but those actions are subject to certain conditions; for example, countries commonly have an age threshold for heritage items (for example, 100 years). In 1834, Greece became one of the first modern nations to pass a patrimony law. Like Italy, Greece is a source country for antiquities and archaeological sites.

The European Union’s (“EU”) first steps towards the uniform protection of cultural heritage at the supranational level began when the Council of the European Union adopted Directive 93/7/EEC on the return of cultural objects unlawfully removed from the territory of a Member State (1993). The Directive did not seek to combat illicit trafficking but, rather, encouraged the protection of national cultural heritage through the creation of accessible return and restitution mechanisms for Member States. In 2014, the European Parliament and Council adopted Directive 2014/60/EU, which expanded protection to all national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value, regardless of their economic value. The new Directive stresses the EU’s “valuable role in encouraging cooperation between Member States with a view to protecting cultural heritage of European significance, to which such national treasures belong.” It requires that each State’s central authorities cooperate and promote consultation with one another. To establish ways for them to interact, UNESCO and the EU have organized training workshops on illicit trafficking for EU Member States, their national law enforcement agencies, and international organizations. These workshops aim to teach national authorities about their fellow Member States’ successful strategies in fighting against the illicit trafficking of cultural objects and to encourage interstate cooperation.

Italy’s patrimony laws

On March 31, 2016, Italy updated its Code of Cultural Heritage and the Landscape (CHC) to enhance the domestic protection of cultural heritage. The current Code strengthens the mechanisms in place for the central government supervision and protection of the country’s cultural property and requires governmental entities to create inventories of cultural property under their administration. Notably, the CHC’s 2016 amendment eliminated the statute of limitations on legal actions for the recovery of cultural property that have been illegally removed from Italy. According to Article 174, anyone who exports cultural property without an appropriate license is subject to a prison term of one to four years, or to a criminal fine of up to 5,165 euros. If the offender is a professional art dealer or someone generally involved in the art market, he/she will be banned from engaging in his professional activity. In addition, Italy’s Civil Code and case law have created a presumption that all antiquities found on Italian soil are considered State property. These goods can either be part of the public domain or inalienable assets of the State. Based on these two principles, Article 91 of the CHC states that cultural objects found underground or on the seabed belong to the State. These presumptions make it significantly more difficult for traffickers and illicit excavators to justify their actions.

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: The American Institute for Roman Culture, “The Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Goods: A Long and Ignoble History” Ancient Rome Live/Amineddoleh & Associates LLC. Last modified 11/09/2021. https://ancientromelive.org/the-illicit-trafficking-of-cultural-goods-a-long-and-ignoble-history/

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 11/09/2021 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.