Petra and the Nabataean Kingdom

by Alaa Ababneh, PhD Candidate at Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona

Petra, the famous rock-cut city in modern-day Jordan, rose to prominence because of its strategic location at the crossroads of major trade routes. Founded in the 4th century BCE, it became a vital center for caravans carrying valuable goods, especially spices and perfumes, from the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean. The Nabataeans, an ancient Arab people who settled in the region, used this position to control trade and accumulate vast amounts of wealth.

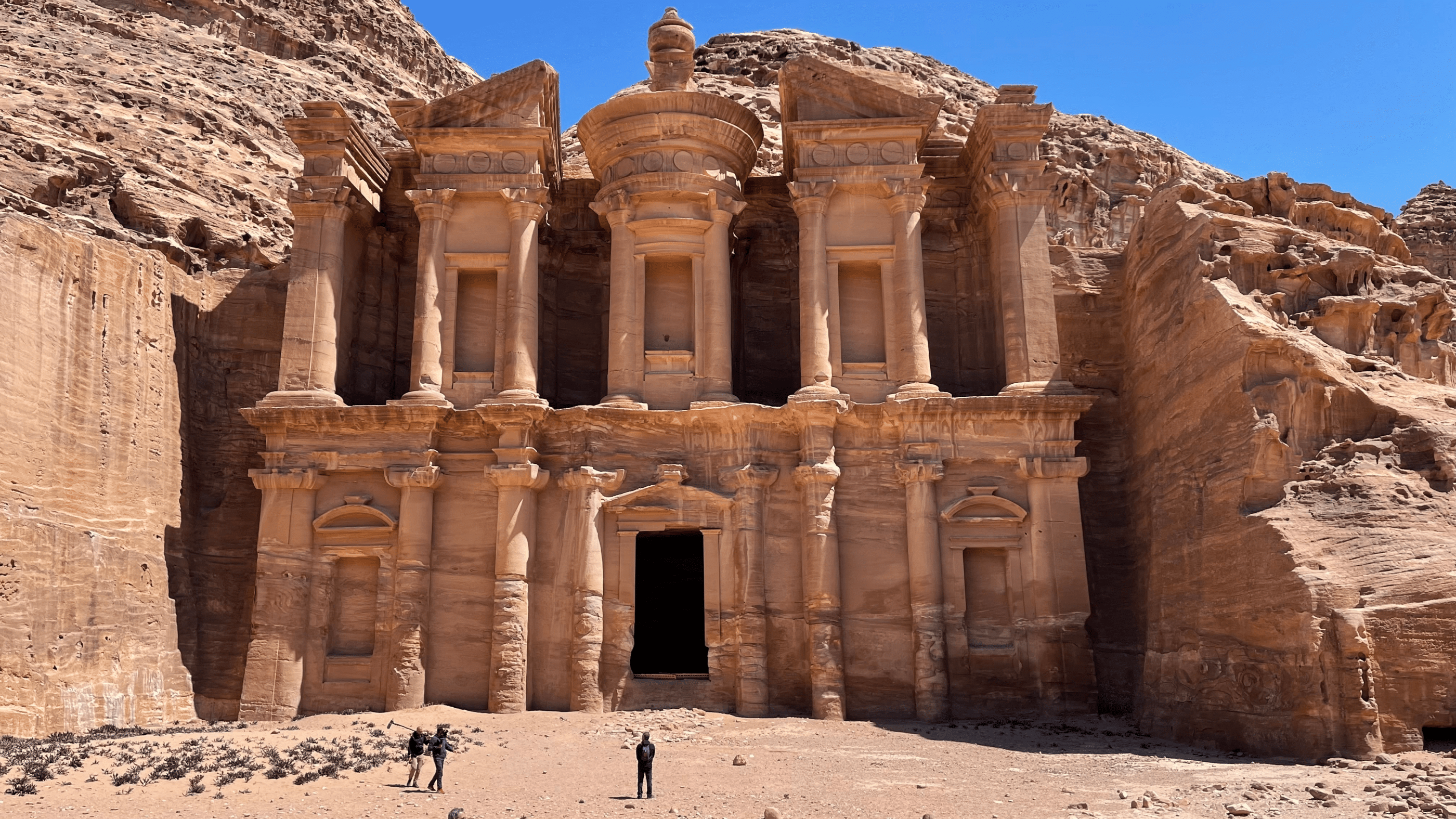

The Nabataeans channeled this wealth into creating a city unlike any other. Petra’s most iconic monuments – temples, tombs, and ceremonial buildings – were carved directly into the vibrant red and pink sandstone cliffs that surround the city. These impressive structures reflect both artistic skill and the resources available to the Nabataean elite.

But Petra’s success was not just about trade. The city thrived in a harsh desert environment thanks to the Nabataeans’ advanced water management techniques. They designed a sophisticated system of underground cisterns and reservoirs to collect and store rainwater. By lining cisterns with waterproof plaster and placing them deep underground, they minimized evaporation and protected their water supply from enemies. This hydraulic ingenuity allowed Petra to support a large population, estimated at between 20,000 and 30,000 people, and sustain agriculture in an arid climate.

Thanks to these innovations, the Nabataeans were able to dominate the spice trade from the 6th century BCE to the 1st century CE. Over time, their kingdom expanded to include parts of modern Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Israel. They also proved to be formidable warriors. In 312 BCE, they repelled multiple attacks by Antigonus I, a successor of Alexander the Great. Later, in 84 BCE, they defeated the Seleucid king Antiochus XII at the Battle of Cana.

By the 1st century CE, the Nabataean Kingdom had reached its peak. It was a regional power both politically and economically. Though it was ruled by kings, Nabataean society was relatively egalitarian. Kings were not viewed as tyrants, but rather as friends of the people. The Greek historian Strabo tells us that during banquets, Nabataean kings would serve their guests. Kings were also accountable to a popular assembly (Strabo, Geography, 16.4.26). Women held significant rights as well – they could own property and take part in religious ceremonies, something not common in many ancient societies.

In 62 BCE, the Roman general Pompey launched a campaign against Petra. King Aretas III avoided destruction by paying tribute and accepting Roman authority. The Nabataean Kingdom became a client state: it retained its kings and some independence but had to pay taxes and help protect Rome’s eastern frontier. This arrangement lasted until 106 CE, when Emperor Trajan formally annexed the kingdom into the Roman Empire. Even after its political independence ended, Petra remained a vibrant cultural center for centuries – its stunning architecture and engineering achievements a testament to the creativity and resilience of the Nabataeans.

Bibliography:

- Alzoubi, Mahdi, Eyad al Masri, and Fardous al Ajlouny. (2013). “Women in the Nabataean Society.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 13, No 1, pp.153-160. https://www.academia.edu/39943706/WOMAN_IN_THE_NABATAEAN_SOCIETY

- Bedal, Leigh-Ann. (2002). “Desert Oasis: Water Consumption and Display in the Nabataean Capital.” Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4), 225–234. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3210851

- Frangié-Joly, Dina. (2016). “Perfumes, Aromatics, and Purple Dye: Phoenician Trade and Production in the Greco-Roman Period.” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies, 4(1), 36–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.4.1.0036

- Joukowsky, Martha Sharp. (1999). “A Brief History of Petra.” Brown University. https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/Petra/excavations/history.html

- Joukowsky, Martha Sharp. (2002). “The Petra Great Temple: A Nabataean Architectural Miracle.” Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4), 235–248. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3210852

- “Petra.” UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/326/

- Schmid, Stephan, Piotr Bienkowski, Zbigniew Fiema, and Bernhard Kolb. (2012). “The Palaces of the Nabataean kings at Petra.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 42, 73–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41622198

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: Alaa Ababneh, “Petra and the Nabatean Kingdom,” Ancient Rome Live. Last modified 5/22/2025. https://ancientromelive.org/petra-nabatean-kingdom

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 5/22/2025 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.