The Ara Pacis, or Altar of Peace, was commissioned by Augustus in 13 BCE to commemorate his victories and celebrate the peace he brought to the Roman world. Completed four years later, it served as both a victory monument and a piece of political propaganda, glorifying Augustus and his reign. While today the monument appears as plain white marble, in ancient times its surfaces were painted in bright, vivid colors.

Located in the northern Campus Martius, just south of the Mausoleum of Augustus, the Ara Pacis was buried over time and rediscovered beneath a Renaissance-era palace. In the 20th century, Benito Mussolini had the monument excavated, reassembled, and displayed in a new museum as part of his effort to link Fascist Italy to the ancient Roman Empire.

Officially, the Ara Pacis was built to honor Augustus’ safe return from Hispania and Gaul in 13 BCE. It was dedicated on January 30, 9 BCE – coinciding with the birthday of his wife, Livia. Its overall message is the celebration of peace, specifically the peace Augustus claimed to have restored after years of civil war.

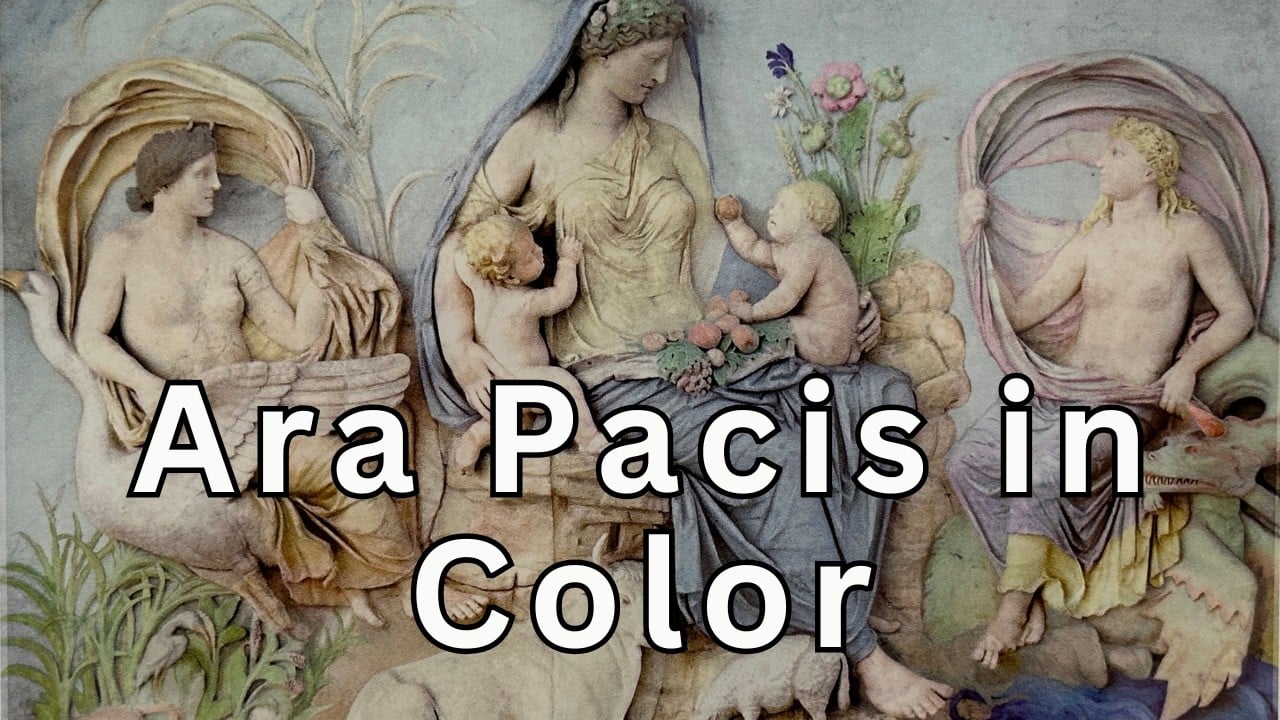

Much of the Ara Pacis’ decoration is carved into its outer walls. The lower section features a detailed scrollwork of acanthus leaves, intertwined with fruits, vegetables, and small animals. This imagery symbolizes fertility and abundance, blessings of peace.

The upper sections of the walls contain a mix of mythological and historical scenes. On the front panels near the entrance are depictions of Rome’s founding myths: Romulus and Remus being nursed by the she-wolf, and Aeneas making a sacrifice. Along the sides of the altar are large processional scenes showing members of the imperial family, highlighting the monument’s dynastic message and Augustus’ role as the founder of a new political order. The rear panels depict further symbols of fertility and prosperity, including the famous Tellus panel showing a seated mother goddess surrounded by animals and plants.

Inside the altar, the decoration is less well preserved. Reliefs of ox skulls hang with garlands of fruits and flowers, likely representing the types of offerings made during rituals. The altar itself may have once been decorated with images of Rome’s conquered provinces, though these details have not survived.

Importantly, all of these reliefs would have been brightly painted. Ancient paints were made by mixing mineral or organic pigments with binders such animal glue or wax. Over time, these organic materials decayed, causing the colors to fade and leaving the marble bare. Colors like purple came from crushed snail shells, Egyptian blue was made from copper compounds, and reds were produced using iron oxide. These colors would have added vivid detail to every figure and design on the altar.

Today, much of the visual richness of the Ara Pacis is lost, as we see only the bare marble. But originally, it was a brilliantly painted monument that conveyed both religious and political messages. The Ara Pacis remains one of the most striking examples of how ancient Roman art used color and design to connect public monuments to imperial power.

Bibliography

- Bradley, Mark. (2009). “The Importance of Color on Ancient Marble Sculpture.” Art History, 32, 427-457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2009.00666.x

- Elsner, John. (1991). “Cult and Sculpture: Sacrifice in the Ara Pacis Augustae.” The Journal of Roman Studies, 81, 50–61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/300488

- Grout, James. “Ara Pacis.” University of Chicago. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/encyclopaedia_romana/romanurbs/arapacis.html

- Lamp, Kathleen. (2009). “The Ara Pacis Augustae: Visual Rhetoric in Augustus’ Principate.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 39(1), 1–24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40232573

- Platner, Samuel. (1929). “Ara Pacis.” In A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (p.30-32). Retrieved from: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/Ara_Pacis.html

- Thornton, M. K. (1983). “Augustan Genealogy and the Ara Pacis.” Latomus, 42(3), 619–628. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41532895

Ara Pacis: an altar erected by the senate in honour of the victorious return of Augustus from Spain and Gaul in 13 B.C., on which the magistrates, priests and Vestals should offer annual sacrifices (reference Latin Library): Cum ex Hispania Galliaque rebus in his provincis prospere gestis Romam redi Ti. Nerone P. Quintilio consulibus aram Pacis Augustae senatus pro reditu meo consacrari censuit ad campum Martium in qua magistratus et sacerdotes et virgines Vestales anniversarium sacrificium facere iussit; ib. VI.20‑VII.4 (Grk.)). The decree of the senate was dated 4th July, 13 B.C. (Fast. Amit. ad IV non. Iul., CIL I2 p244, 320: feriae ex s.c. quo[d eo] die ara Pacis Augustae constituta est (begun) Nerone et Varo cos.; Antiat. ib. 248), p31 and dedicated 30th January, 9 B.C. (Fast. Caer. Praen. ad III kal. Febr., CIL I2 p212, 232; Fast. Verul. ap. NS 1923, 196; Ov. Fast. I.709‑710; Act. Arval. a. 38, CIL VI.2028; a.39 (?) ib. 32347a; HJ 612). Which of these ceremonies constitutes the setting of the procession represented on the reliefs is doubtful. The altar is represented on coins of Nero (Cohen 27‑31), and of Domitian (ib. 338), but is not mentioned elsewhere either in literature or inscriptions (for the discussion of these coins, see Kubitschek ap. Petersen, Ara Pacis 194‑196, and in Oesterr. Jahresh. 1902, 153‑164; cf. SR 1913, 300‑302, and also BM Imp. Nero, 360‑365).

This altar stood on the west side of the via Flaminia and some distance north of the buildings of Agrippa, on the site of the present Palazzo Peretti Fiano-Almagià at the corner of the Corso and the Via in Lucina. Fragments of the decorative sculpture, found in 1568, are in the Villa Medici, the Vatican, the Uffizi, and the Louvre; others, found in 1859, are in the Museo delle Terme and in Vienna. They were recognized as parts of the same monument by Von Duhn and published in 1881 (Ann. d. Inst. 1881, 302‑329; Mon. d. Inst. XI pls. 34‑36; for a fragment found in 1899 cf. NS 1899, 50; CR 1899, 234). Systematic excavations in 1903 under the palazzo (NS 1903, 549‑574; CR 1904, 331) brought to light other remains of the monument, both architectural and decorative. The work was not finished, but arrived far enough to permit of a reconstruction which is fairly accurate in its main features, although there are still unsolved problems in connection with the arrangement and interpretation of the reliefs. Most of the fragments then found are in the Museo delle Terme (PT 65‑68), though others still remain on the site.

The altar itself was not found. It stood within an enclosing wall of white marble, about 6 metres high, which formed a rectangle measuring 11.625 metres east and west, and 10.55 north and south (NS 190, 568). In the middle of the east and west sides were entrances flanked with pilasters, and other pilasters stood at each angle of the enclosure. The inside of the enclosing wall was decorated with a frieze of garlands and ox-skulls above a maeander pattern, beneath which was a panelling of fluted marble. A frieze of flowers and palmettes adorned the outside of the enclosure and above this on the north side were reliefs representing the procession in honour of the goddess, with many figures of the imperial family and the flamines, and, on the south, senators, magistrates and others (Reinach, Répertoire des Reliefs I.232‑237).º On the north side of the east entrance was a group of Honos, Pax and Roma, while on the south was a relief of Tellus, or Italia (Van Buren, JRS 1913, 134‑141). The dates forbid us to suppose that the Ara Pacis inspired Horace when he was writing Carm. Saec. 29‑32; and it is therefore probable that both were inspired by a lost monument with a group of Tellus, which is more closely reproduced in a relief at Carthage (Loewy in Atti del Congresso di Studi Romani, Rome 1928). The west entrance was flanked on the north by a group of Mars and Faustulus at the Ficus Ruminalis (?) and on the south by Aeneas sacrificing when he found the sow. An ingenious attempt has been made to explain the architectural and decorative scheme of the enclosure as a reproduction in marble of the temporary wooden enclosure of the site and the ceremony p32 of consecration on 4th July, B.C. 13 (Pasqui, SR 1913, 283‑304). The reliefs of this altar represent the highest achievement of Roman decorative art that is known to us. (For the discussion and interpretation of the monument and its reliefs, see Petersen, Mitt. 1894, 171‑228; Sonderschrift d. oesterr. Inst. II.1902, published separately as Ara Pacis Augustae, Vienna 1902; Mitt. 1903, 164‑176, 330; Oesterr. Jahresh. 1906, 298‑315; Reisch, WS 1902, 425‑436; v. Domaszewski, Oesterr. Jahresh. 1903, 57‑65; Gardthausen, Der Altar des Kaiserfriedens, Ara Pacis, Lpz. 1908; Dissel, Der Opferzug der Ara Pacis, progr. Hamburg, 1907; Strong, Scultura R. 17‑65; Cannizzaro, Boll. d’ Arte, 1907, 1‑16; Wace, PBS V.176‑178; Sieveking, Oesterr. Jahresh. 1907, 175‑190; Beiblatt 107; Mitt. 1917, 90‑93; Studniczka, Abh. d. sächs. Gesellsch. 1909, 901‑944; Wagenvoort, Med. 1921, 108; Rizzo, Atti Acc. di Napoli, 1920, 1‑21; Capitolium, II.457‑473; Mon. Piot, xvii (1910), 157‑187.)

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Ara Pacis Augustae Hardcover – 1968

The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Imagery of Abundance in Later Greek and Early Roman Imperial Art Hardcover – May 26, 1995

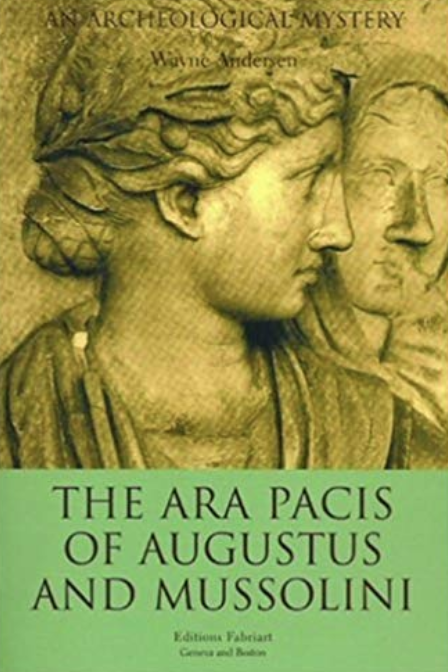

The Ara Pacis of Augustus and Mussolini Paperback – April 1, 2003

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: Darius Arya, The American Institute for Roman Culture, “Ara Pacis Augustae” Ancient Rome Live. Last modified 07/26/2025. https://ancientromelive.org/ara-pacis-augustae/

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 10/24/2019 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.