Start with our video overview:

The Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine which lies along the northern Sacra Via was the largest and last basilica to be completed in ancient Rome. Its construction was initiated by the emperor Maxentius in 306 CE where the Horrea Piperataria of Domitian had stood. It was adapted and completed by Constantine, after 313 CE. The basilica was originally part of Maxentius’s architectural programme to present himself as a new founder of Rome; after he was defeated at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, it was reappropriated into the visual system of his successor, along with the nearby Arch of Constantine which celebrated this victory.

The Basilica of Maxentius followed atypical forms and resembled a central hall of an imperial bath complex due to its vaulted concrete roof. The imposing basilica stood on a concrete rectangular platform measuring 100 by 65 meters, with a central nave 25 meters high and the side aisles 24.5 meters high. Still partly visible is the polygonal coffered ceiling, whereas nothing of the nave remains. The nave roof connected to Corinthian columns around all sides, while the walls and floor were marble, the latter being polychrome with geometric patterns. On the other hand, the side aisles were divided into three parts by arches that spanned the nave; along the piers stood eight monolithic marble columns around 15 meters high and five meters around, the sole survivor of which now stands before the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

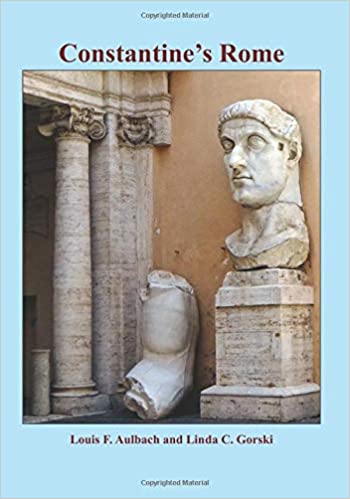

To the blueprint created by Maxentius, Constantine added a second entrance to a columnated porch with a semi-circular apse, producing the impression of three parallel halls from both entrances. In the original apse, which had a diameter of 20 meters, he placed the colossal statue of himself which is now preserved in fragments in the Capitoline Museums following its excavation in the fifteenth century. The basilica connected to the Forum of Vespasian at its north-western corner, blocking the previous thoroughfare between the Roman forum and the senatorial neighborhood of Carinae which was therefore replaced by raising the street level and opening a four-meter-wide passage beneath the new building. After the end of the imperial period, this passageway acquired associations with thieves and was closed in the sixteenth century for the construction of a new district.

Between the fifth and sixth centuries, the ancient pavement was again raised, and the significant transitions of this period are evidenced by the recording of the basilica as a temple in the sixth century; clearly, it had lost its original purpose by this time. Despoliation of the imposing structure soon followed, with its bronze roof tiles transported to St Peter’s Basilica in the seventh century. Natural disasters also played a role in its ruination, as the nave is thought to have collapsed in the earthquake of 847 which also destroyed much of the nearby Colosseum. This resulted in a necropolis developing in the eleventh century, by which time the area was on the fringe of one of the sparsely populated settlements which occupied medieval Rome. Although the remains are a shadow of the former structure, they maintain an imposing presence within the archaeological park and even hosted the wrestling events of the 1960 Olympics.

References

- Claridge, “Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide”, (Oxford 2010), 239-50; 487.

- Platner, “A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome”, (Chicago 1929).

(Pol. Silv. 545), Constantiniana (Chron. 146; Not. app.) or Nova (Not. Reg. IV.): begun by Maxentius but completed by Constantine (Aur. Vict. Caes. 40. 26: adhuc cuncta opera quae magnifice construxerat urbis fanum atque basilicam Flavii meritis patres sacravere) on the north side of the Sacra via, a site previously occupied, in part at least, by the horrea Piperataria (Chron. cit.) of Domitian.

Read more:

It was the last of the Roman basilicas, which it resembled less than it did the halls of the great thermae. Its proper designation appears to have fallen into disuse at an early period, for in the sixth century it was called templum Romae; 2 (LPD i. 280; Mel. 1886, 25 ff.; cf. however, BC 1900, 303), and in the seventh when Pope Honorius took its bronze tiles for the roof of St. Peter’s (LPD i. 323; cf. BC 1914, 106). The south aisle and the roof of the nave probably collapsed in the earth- quake of Leo IV in 847 (LPD ii. 108); see VENUS ET ROMA, TEMPLUM).

The basilica stood on an enormous rectangular platform of concrete 100 metres long and 65 wide, and consisted of a central nave 80 metres long, 25 wide and 35 high, with side aisles 16 metres wide and 24.50 high. These aisles were divided into three sections by walls pierced by wide arches and ending on each side of the nave in massive piers. In front of these piers and at the corners of the nave were eight monolithic columns of marble, all of which have been destroyed except one that was removed by Paul V in 1613 to the Piazza di S. Maria Maggiore, where it now stands (LS ii. 209; JRS 1919, 180). The height of the shaft of this column is 14.50 metres, and it is 5.40 metres in circumference. On the piers rested the roof of the nave, divided into three bays with quadripartite groining. The ceiling was decorated with deep hexagonal and octagonal coffers. For the entasis see Mem. Am. Acad. iv. 122, 142.

The facade of the basilica as built by Maxentius was towards the east, and at this end was a corridor or vestibule, 8 metres deep, which extended across the whole width of the building. From this vestibule there were five entrances into the basilica, three into the nave, and one into each of the aisles. A flight of steps led up from the street in front to the vestibule, which was adorned with columns. At the west end of the nave was a semicircular apse, 20 metres in diameter, in which the fragments of the colossal statue of Constantine, now in the Palazzo dei Conservatori, were probably found in 1487 (HC 242; Cons. 5, il ff.). The statue probably sat in this apse, which would have been its natural place.

Constantine spoilt the original conception of the building when he constructed a second entrance from the Sacra via in the middle of the south side, where he built a porch with porphyry columns (?) and a long flight of steps (Ill. 10). Opposite this new entrance he constructed a second semicircular apse in the north wall, as large as that at the west end of the nave but lower (PBS ii. pls. 16, 59; CR 1905, 76). Thenceforth the basilica produced the same impression-of three parallel halls-whether one entered it from the south or from the east.

Besides the foundation, which has been almost wholly uncovered, the north wall and the north aisle-or, as it rather appears, the north sections of the three halls regarded as running north and south-are still standing. The semicircular apse in the central hall contains sixteen rectangular niches in two rows, with a pedestal or suggestus in the centre. A marble seat with steps runs round the apse, which was separated from the rest of the hall by two columns and marble screens, thus forming a sort of tribunal. Nothing of the nave remains except the bases of the great piers. The core of the porch and of the flight of steps leading down to the Sacra via is still visible, and several fragments of the porphyry columns have been set up, but not in situ. Of the pavement of slabs of marble considerable fragments have been found (Mitt. 1905, 117).

The material employed in this basilica was brick-faced concrete (AJA 1912, 429-432), and the great thickness of the walls-6 metres at one point at the west end-and the enormous height and span of the vaulted roof made it one of the most remarkable buildings in Rome. The magnificence of its interior decoration was commensurate with its size and imposing character. It was modelled on the central halls of the great thermae.

The north-west corner of the basilica joined the wall of the forum of Vespasian, thereby cutting off the previously existing thoroughfare between the forum Romanum and the district of the Carinae. Maxentius therefore constructed a passage-way under the north-west corner of the building, about 4 metres wide and 15 long. In the Middle Ages this was known as the Arco di Latrone 3 from its dangerous associations (JRS 1919, 179). For the road round the back of the north-eastern apse see LS ii. 211 ; PBS ii. 17.

For the older literature and illustrations, see especially: Nibby, Del Foro Romano, della Via Sacra, dell’ Anfiteatro Flavio, Rome 1819, 189 ff.; Del Tempio della Pace (under which name it was generally known before his time) e della Basilica di Constantino, Rome 1819; Roma antica ii. 238 ff.; Canina, Edifizi ii. pls. 129-132; M61. 1891, 161- 167; Mitt. 1892, 289; more recent: Reber 392-397; Middleton ii. 224-229; Thed. 343-348; Petersen, Vom alten Rom 31-53; HC 227-231; HJ 11-14; Durm 174, 175, 232, 259-260, 265; NS 1878, 132, 163; 1879, 14, 263, 264,312,313; RE iv. 961-962; D’Esp. Fri.i. 100; ii. 100; DuP 105-107 ; Toeb. i. 117-130; ZA 109-Ill; RA 211-215; DR 419-428; ASA 84, 85.

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: Darius Arya, The American Institute for Roman Culture, “Basilica Constantini” Ancient Rome Live. Last modified 04/06/2021. https://ancientromelive.org/basilica-constantini/

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 04/06/2021 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.