Myth, history, and archaeology smash together in the northwest corner of the Roman Forum. Different sources place major events from Rome’s quasi-mythical early history in the area that is today occupied primarily by the Arch of Septimius Severus and the Church of Sant’Adriano al Foro (itself a 7th century CE reconstruction of the Curia Julia ). The earliest structure attested in this area is the Vulcanal, a shrine to the god Vulcan that marked the spot (again, allegedly) where Romulus and the Sabine King Titus Tatius made peace. Associated with the Vulcanal is the archaic cippus, a stone bearing an inscription, which was covered over during Caesar’s renovation of the area with black marble paving (called the “Lapis Niger” or “the Black Rock”). Early Imperial writers recognized the sacred nature of this spot, but were uncertain about the specifics. The cippus itself is more illuminating; although the language is extremely archaic, the words for “king” and “crier” are discernible and in turn suggest that the area was an early gathering place.

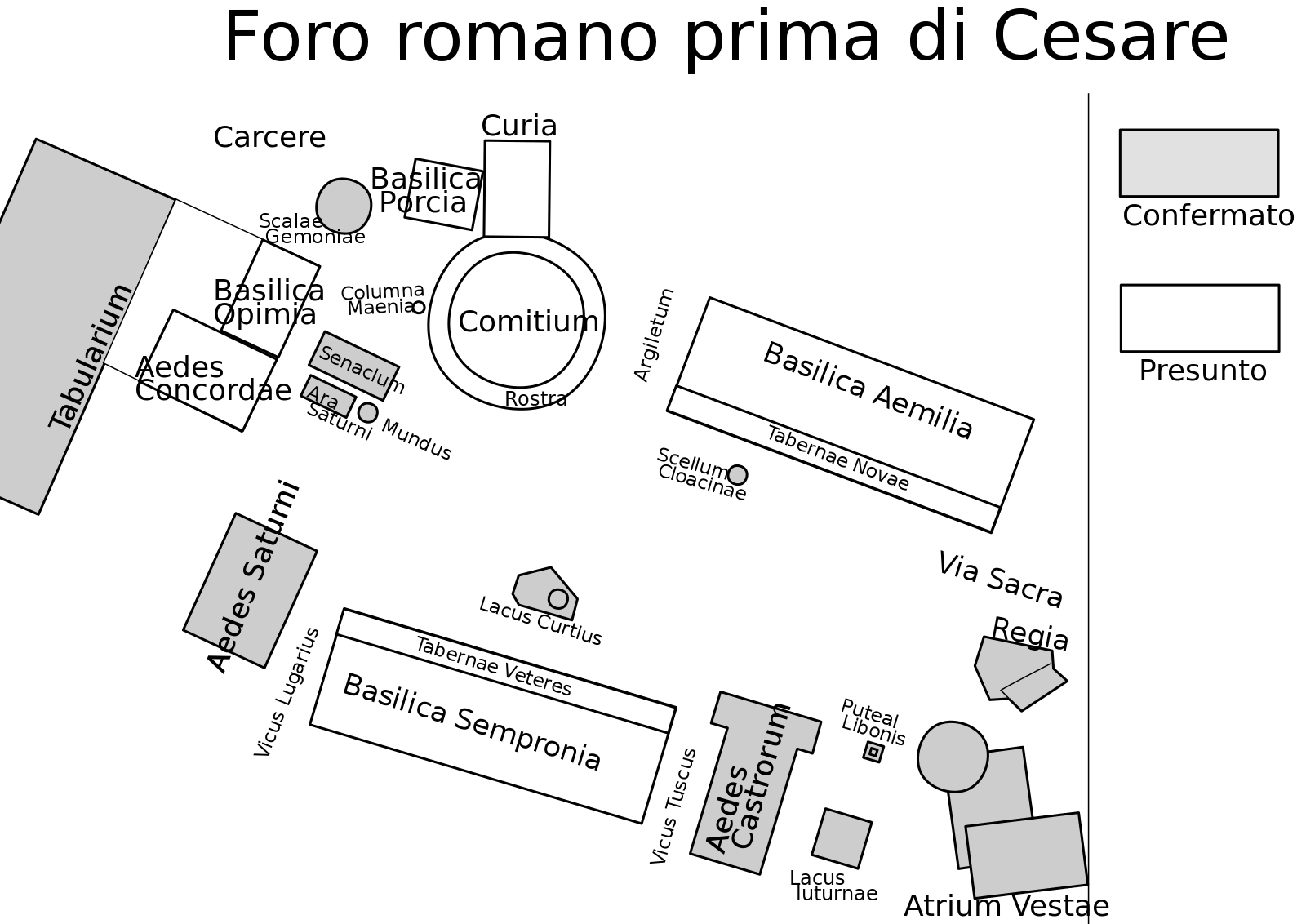

Roman Forum prior to Caesar. Credit Wikipedia

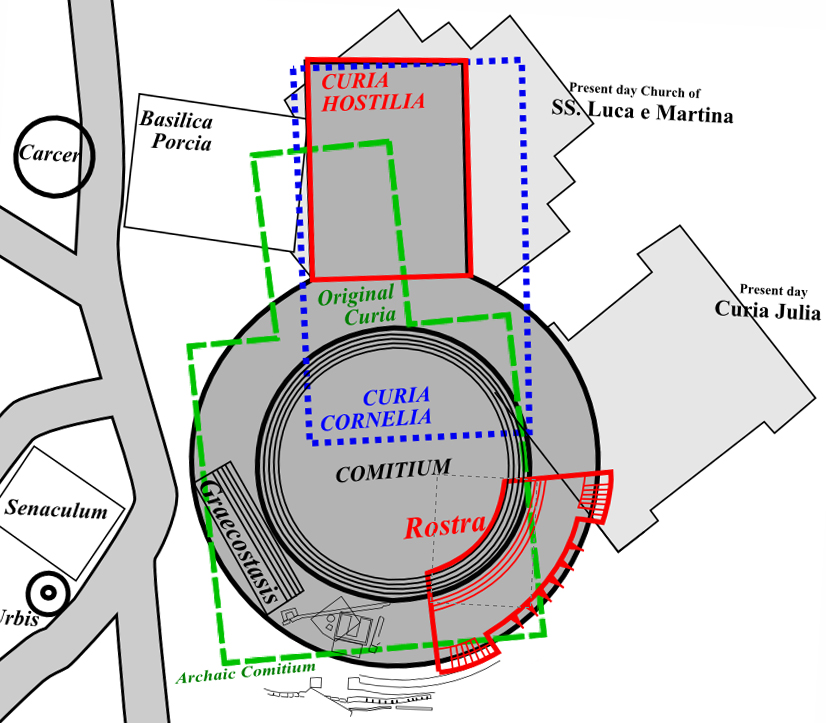

This plan depicts the relationship between the original Curia and Comitium, which included the areas of the rostra, Graecostasis, and Lapis Niger. According to most of the traditional assessments, the original Curia Hostilia was under SS. Luca e Martina, and the Comitium area occupied the area in front of imperial Curia Iulia. Credit Wikipedia/Mark Miller

Before discussing the functions of the Comitium as it existed for most of the Roman Republic we should put it in its place. The Romans called the building in which the Senate convened the Curia Hostilia because they believed it to have been built by Tullus Hostilius. While its association with Rome’s third king was certainly a later, fictional origin story for the Curia, archaeological evidence does show a structure in this place going back to the late 7th century BCE. The Curia Hostilia took up much of the Comitium’s northern boundary. The southern boundary of the Comitium was the speakers’ platform. Archaeological evidence suggests that a stone podium existed here from as early as the early fifth century BCE, but it did not get its familiar name, the Rostra, until the mid-fourth century. In Latin “rostrum” means “beak” and refers to the metal ramming beak attached to ancient warships. After the consul Gaius Maenius defeated Antium in 338 BCE the beaks from Antium’s ships were fixed to the speaker’s platform, giving the podium its name.

While this area of the Forum – including the Curia Hostilia and the Rostra – is often referred to collectively as the Comitium, that actual Comitium was the gathering space in between Curia and the Rostra. Certainty about its shape and appearance has proved elusive. One popular reconstruction – advanced most prominently by Filippo Coarelli – suggests that from the early third century BCE on the Comitium was a circular, stepped area, but this view was based largely on comparison with other fora in Italy (see the images from the Comitium at Paestum). More recently, however, scholars have drawn attention to evidence against a circular Comitium and argued for a more triangular shape. Given that its shape is uncertain there is no firm consensus on how many people the Comitium could hold; estimates range from 1,000 to 20,000 and naturally depend on how one envisions the shape of the space. We will discuss other adjoining structures below, but this triad – Curia, Comitium, Rostra – dominated the complex.

The Comitium was one of the most important political spaces in republican Rome. The first century BCE polymath Varro tells us (LL 5.155) that it took its name from the Latin verb coire, which means “to come together.” This makes sense if in fact the theories about the Comitium as a meeting space in the regal period are true, but it is certainly reflective of the role of the Comitium during the Republic. Rome’s early, ethnically-defined Curiate Assembly met here, as did the more familiar Tribal Assembly, which voted to elect quaestors and aediles and to pass laws. Another structure associated with the Comitium, The Basilica Porcia, also served an important political function. From the middle of the second century the Basilica Porcia stood next to the Curia Hostilia on the west side. Up to this point in time this portion of the Forum near the Comitium was still populated with shops and private residences, but in 148 BCE one of republican Rome’s most famous statesmen, Marcus Porcius Cato (often called “Cato the Elder”), oversaw the purchase (and destruction) of these structures and the construction of the basilica. Augustan architect Vitruvius writes (5.1) of basilicas as buildings valued for their multipurpose potential; when the weather turned cold, for example, basilicas could give people an indoor space to trade. Because the Roman Forum boasted multiple basilicas, the Basilica Porcia was able to specialize in function: it was where the Tribunes of the Plebs could be found. These magistrates were mediating figures between the Senatorial elite and the People, and were tasked to ensure that magistrates could not use their power to violate the rights of a citizen. Those who wished to seek the aid of the tribunes – one of a Roman citizen’s most sacred rights – could come to the Basilica Porcia to find the tribune’s benches and plead their cause. Similarly, Tribunes could address a crowd in the Comitium.

The Augustan remains of the Lapis Niger, which was originally enveloped by the Comitium in the Republican, pre-Caesarian era.

Politics was not the only business conducted in the Comitium. In his Curculio, the Roman comic playwright Plautus has one of his characters describe the Forum, and he refers to the Comitium as a place of liars (in Latin, “periuri”). This is a joke referring to the fact that the Comitium housed Rome’s law courts and trials. On the eastern side the Comitium was bordered by yet another platform, the praetorian tribunal, where the praetors would hear legal cases and publicize praetorian edicts. Additionally, attached to the Rostra was a copy of the Twelve Tables, the basis of Roman law. These served the double function of being available for consultation during cases in the Comitium and commemorating the victory of the People in the “Struggle of the Orders,” during which they obtained access to the laws. As the need for more space for trials became more pressing, the basilicas of the Forum also housed court cases.

If you were awaiting trial or found guilty in one, you didn’t have far to go either. Directly adjoining the Comitium on the west was the Tullianum, the city’s main prison. Incarceration in a prison (unlike today) was not a punishment in republican Rome; rather the Tullianum was a place to hold prisoners before their trial and (when necessary) in between being found guilty and execution. This is also where captured enemy leaders would be held before their ritual execution during a triumph. Caesar’s Gallic foe Vercingetorix, for example, spent six years in the Tullianum waiting for Caesar’s triumph. The combination of the public display of the laws – a right hard-won and dearly cherished by the Roman People – combined with the presence of the Tribunes’ benches meant that citizens in need of legal help (or in legal trouble) could expect a trip to the Comitium.

As the city’s most important political space, the Comitium was highly decorated with symbolically-powerful monuments, and not all of its statues were of the familiar image of a Roman general. For example, a statue of Attus Navius, a famous augur from the regal period, was placed in the Comitium next to a sacred fig tree named after him. Likewise, not all the people celebrated with statues in the Comitium were Roman. Pliny the Elder also mentions statues of philosophers Hermodorus of Ephesus (whom the Romans credited as a consultant in the creation of the Twelve Tables) and Pythagoras (whom legend – but certainly not reality – tells us was a tutor to Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king). We also hear of a statue of 5th century Athenian statesman Alcibiades (See Pliny NH 34.20-26 for more). Some of the statues even commemorated mythical figures; there was a statue of the mythological satyr (half-goat/half-man) Marsyas on the Rostra.

In addition to these fascinating examples, the Comitium also (naturally) served as a reminder of Rome’s military success. In celebration of the same victory over Antium that produced the beaks of the Rostra, a column was also erected to celebrate the victorious general Gaius Maenius (called the Columna Maenia). It is possible that the column was originally in the atrium of Maenius’ house. Pliny also tells us that the Comitium housed Rome’s first historical fresco; the side of the Curia Hostilia was painted with a mural depicting the victory of Manius Valerius Maximus Corvinus Messalla over the Carthaginians and Syracusans during the First Punic War in 263 BCE. The painting was so beloved that renovations of the Curia undertaken by Sulla in early first century BCE took care to preserve it.

Having so much important history, function, and symbolism crammed into a relatively small space makes it a particularly fascinating location for considering interaction and ideology in the Roman Republic. The Romans defined their state with the efficient and familiar acronym SPQR, which shortens “Senatus Populusque Romanus” meaning “The Senate and People of Rome.” The functioning of the Republic as a form of government depended on how these two groups worked together (and against each other), and the Comitium was – as its name suggests – an important place where both parties met. Depending on how one understands this relationship, the Comitium can be interpreted in different ways. On at least an ideological and rhetorical level, the Roman People had relatively immense political power; through their control over the election of magistrates and the passing (or rejecting) of legislation, few decisions at Rome were made (officially) without the approval of the People. To this end, the Comitium was obviously a space that celebrated the rights and involvement of the People. We have seen this already with examples like the posting of the Twelve Tables and the establishment of the tribunes’ benches, but we should not overlook the obvious. The Comitium was a place where the government communicated with the People and vice versa, and that the main gathering place was located directly next to the senate house put pressure on the Senate to communicate well. In fact, when the Senate had made a decision on a given matter a representative would have to cross the Comitium in order to mount the Rostra, undoubtedly a daunting task if the people gathered in the Comitium felt like you were about to deliver bad news. On a symbolic level then, the space of the Comitium was at the heart of the Roman constitution.

Some scholars have argued, however, that this account of the People’s influence in politics was more convenient fiction than reality, and that the senatorial elite held an oligarchic grip on the administration of the city. The space of the Comitium has featured prominently in their arguments. On the one hand, they point out that the number of people able to fit in the Comitium was small (see above), and the smaller the accepted estimate, the less legitimately the crowd in the Comitium could claim to represent the Roman People collectively. Of course, other public spaces in the Forum held much larger numbers, and by the late Republic the Comitium’s status as a meeting place was much more ceremonial than practical. In the mid-second century BCE the crowd in the Forum so heavily outnumbered that in the Comitium that speakers – controversially – began to turn around on the Rostra. More metaphorically, others have placed emphasis on the structures themselves and suggest that the Curia Hostilia’s looming presence within the Comitium represented the hegemony of the men who met within it. These significantly divergent interpretations of the space show just how important it was for understanding Roman politics.

Much of the Comitium was destroyed rather rapidly in the late Republic. The Curia Hostilia was renovated by Sulla and retitled the Curia Cornelia (Sulla’s family nomen was Cornelius). But the Curia Cornelia did not last long, it was burnt down in 52 BCE during the funeral for slain tribune P. Clodius Pulcher. With a clean slate, Julius Caesar reimagined the space – including the relocation of the Rostra away from the Comitium and a new Curia Julia.

Written by: Noah Segal, University of California Santa Barbara

Bibliography

While its assertions can at times be questionable (i.e. overly optimistic or imaginative) the Atlas of Ancient Rome is a beautiful, elegant, and informative resource. It is edited by two giants of Roman archaeology, Anrea Carandini and Paolo Carafa, and has been recently translated into English (Princeton University Press, 2020). It is an immensely fun source to use, and will eventually be put entirely online.

An excellent resource for both visual aids and information is the website of the Digitales Forum Romanum Project, run by the Winckelmann-Institut of the Humboldt-Universität of Berlin.

Entries in the Oxford Classical Dictionary (available here) are also a good place to start for those interested in learning more about these sites.

Carafa, Paolo. 1998, Il comizio di Roma dale origini all’età di Augusto, Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

Coarelli, Filippo. 1983 (v.1) & 1985 (v.2), Il Foro Romano

See also his entry on the Comitium in the Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, volume 1 (ed. Steinby, 1993. Edizioni Quasar).

Morstein-Marx, Robert. 2004, Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic, Cambridge University Press.

Mouritsen, Henrik. 2017, Politics in the Roman Republic, Cambridge University Press.

This content is brought to you by The American Institute for Roman Culture, a 501(C)3 US Non-Profit Organization.

Please support our mission to aid learning and understanding of ancient Rome through free-to-access content by donating today.

Cite This Page

Cite this page as: The American Institute for Roman Culture, “Tue Comitium, Quintessential Structure of Republican Rome” Ancient Rome Live. Last modified 01/20/2021. https://ancientromelive.org/tue-comitium-quintessential-structure-of-republican-rome/

License

Created by The American Institute of Roman Culture, published on 01/20/2021 under the following license: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.